Of Water and Roots: The Power of the Werewolf Leaf

0

15

0

These are my notes for a talk given last night at Sana Sana Seminar at City Alchemist in Austin.

Mèt Gran Chimen

Nou prale la sous-o

Papa, nou pral chèchè dlo

Kounye-a lè zanfan yo

X2

Lè n a tounen, n a pase fey nan gran bwa

Gran bwa ile

X2

La sous o, nou prale

Gran chimen baryè nou a

Master of the Great Road,

We’re going to the Source.

Papa, we’ll look for water

Now, in the time of the children.

When we return, we’ll pass the leaves in the Great Forest,

Great Forest of the Island.

The Source, we’re going.

Great Road, Our Gate.

-From Priye Ginen, as recorded by Wawa Rasin Kanga

My godmother told me to make sure I tell you that Vodou, above all else, is about community. She said, we don’t care if you’re black, white, rich, poor, we don’t care what religion you are or where you come from, we are here to help. That’s what it’s all about. She adopted me into her family, maybe a family that I sprang from and strayed from long ago. I’ve been welcomed back in. And as soon as you touch this tradition, you become family. It’s my responsibility to treat anyone I meet under the auspices of this tradition as family. I read your cards, you’re family. You come into my shop, you’re family. And so Vodou weaves all life together, because it embraces everything, includes everything and everyone.

History

Vodou comes from Africa. The word Vodou comes from Vodun, which means Spirit in the Fòn language of West Africa, modern day Benin.

But the Vodou we’re talking about today has undergone a galvanizing transformation since it left Africa, like a metamorphic rock is changed forever when exposed to extreme heat and pressure. The Vodou I speak of today started to take shape in the belly of slave ships as they left land and made their way over the water. That experience woven through every part of the tradition.

The victims of state sanctioned kidnappings, prisoners of war, political enemies, anyone who needed to be disappeared by the ruling class (who had signed contracts with European slavers) were rounded up and forced into the bellies of ships and taken through the middle passage. They came from all walks of life. Some of them chose to jump ship and meet a watery death rather than see what awaited them at the end of the trip across the ocean. We’ll talk more about them later.

Those that did arrive on the island that now holds Haiti and the Dominican Republic— called Ayiti by its original Taino inhabitants, then Santo Domingo by the Spanish, and then San Domingue by the French— were put to work on plantations. On average, they would survive about a year of work. The French in particular had done the math and found it more economical to treat them as disposable and work them to death than to give them sufficient food and rest to procreate. They could just sail back to Africa and get more. But over the centuries, the original ports started to run out of slaves to supply the colony with, and the slavers moved down the coast from West Africa to West Central Africa. One by one the communities were depleted and displaced to the now almost exclusively sugar plantations of Saint Domingue. There, under the harshest of conditions, people from all over Africa met each other. They didn’t speak the same languages, and didn’t know all of each others’ spiritual traditions or spirits. But in the spirit typical of Africa in general, they were willing to learn and freely adopted the spirits of foreigners if they seemed helpful. And they needed all the help they could get. So a shared pantheon began to develop.

All of this had to happen in secret, because the slaveowners would not permit them to practice African religions. They gave them one day per year off- Easter- so yesterday would have been the day off- to engage in their own cultural practices. The rest of the time they were forced to be Catholic.

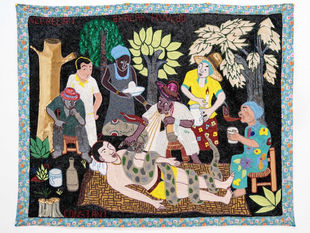

So, with ingenuity and resilience, they embraced catholic* imagery as an expression of their own spirits and beliefs. To a certain extent they did it for preservation. They are sometimes called masks of the spirits. They used catholic images that corresponded with their own deities as a point of connection, since they were not allowed to use their traditional fetishes. For example, Saint Patrick became connected with Papa Danballah, the ancient, seminal, ancestral snake deity that they brought from West Africa.

(*I’m not capitalizing catholic here, because I really feel the meaning of catholic as “universal or all embracing” truly applies here… I think it also bears mentioning that this fusing of catholicism with preexisting spiritual systems was nothing new. It was basically the technique by which catholicism spread in Europe, and why the word catholic is used in the first place.)

It wasn’t all make believe, though. They saw cosmological connections between the catholic worldview and their own, perhaps more profound than the colonizers even imagined. They, too, believed in a single creator god, and they, too, believed in spirit intermediaries between that remote, somewhat indifferent parent of everything and human beings, which Roman Catholics call Saints.

They also acknowledged that their African deities in their old form— which in many cases were the deities of the ruling class that sold them for profit— had not protected them. So Vodou swallowed the protective power of the catholic imagery of the colonizers who had overpowered them, and made it its own. This was an act of resistance. All inclusions of catholic rites in Vodou can be read in this way. The catholic imagery, and even prayers from the Roman Catholic mass, became a pattern capable of drawing their spirits down, even though the colonizers had attempted to destroy and replace them.

Herbalism is also a big part of this tradition. There were also maroons, escaped slaves living in the forest who had learned local botany from, legend has it, communities of Tainos who were continuing to live there, where the colonizers couldn’t reach them.

The spirits of the dead were also important in the religious systems that were brought from Africa, and in Saint Domingue, they were standing on a mountain of the dead. First the Tainos, many of whom had chosen suicide or succumbed to smallpox; then the enslaved people who had been worked to death before them, and all the ancestral spirits they brought with them from Africa. It is said that all these dead fought in the Haitian Revolution.

New spirits emerged as well, ones that were not directly traceable to Africa. Some of the older African deities were sometimes state sponsored, handed down to the people from the same royalty that sold them off. They were elevated principles, but not particularly helpful in an emergency. And this was an emergency. They needed spirits who would fight by their side, come to their aid with immediacy and fiery efficacy.

Then the revolution began. At a legendary ceremony in Bwa Kay Iman, two spirits came down- Ezili Danto and Papa Ogou. They vowed to help liberate the Haitian people. After the revolution, Haiti became theirs.

There was no going back to Africa.

Spirits

The spirits, and the dead, of Vodou live under the water in a mythical land called Ginen. Ginen is in another dimension. It is the nostalgic, longing-filled image of the Africa the people were taken from, an Africa that does not exist anymore in our dimension. The people who jumped overboard live there, the ancient spirits of Africa live there, your departed loved ones, your child who died in childbirth or your mother who died in childbirth, they all live there. When you remember them, communicate with them, it’s like looking through water. Ginen is the spirit world, but when we think about how we process memory, how we return to times gone by, or how we project ourselves into the future, it’s watery. When we remember what it was like to be a child, we remember a watery time. Dreams are watery too, the quality of entering a dream is like entering the water, where everything is fluid, faces swarm and shift and morph into other faces, messages drip with symbolism, everything is possible. It’s also the creative, imaginary realm, where things swarm first before they are born into this reality.

We call the spirits the Lwa. Lwa means Law in Kreyòl. Although they have ties to natural elements, and even specific natural sites in Africa, are not nature spirits. It would be more accurate to say they are laws of human nature. They themselves are human, more human than human. When people see them in vision, they are often very large human forms. The purpose of Vodou ceremony is to get them to come down into the head of one of the participants. Drumming, singing, dancing, offerings, colors, certain modes of dress are all aimed at this. Once the spirit comes down, they consult, they reprimand, they embrace, they enjoin, and they heal. Then they go back to Ginen. All of ceremonial Vodou is done with this aim of calling down and communicating with the Lwa.

On a personal level, through altar work, we create portals of entry, or pwen, for the Lwa. We speak to them, we give them offerings, we decorate according to their taste and colors, we sing to them. We might ask for help with healings, and that help might come in dreams, another portal of communication between the human and spirit worlds.

We put our roots down into the water to reconnect with Ginen, to reconnect with the Source.

The Plant

Kalanchoe pinnata is known as fey lougawou in haiti.

Lougawou translates directly to werewolf, but when my godmother talks about the lougawou that exist in the here and now, she means people with bad energy, harmful people. The plant is called lougawou because it is said to keep lougawou out of your house. It’s a spiritual protector, as is aloe in some traditions. With a fey lougawou growing in your home, no one can enter without your permission. This caveat is characteristic of the sense of personal responsibility in this tradition. It’s up to you to be a good enough judge of character to know who you should invite in and who you shouldn’t. Otherwise, the fey lougawou won’t do anything to protect you.

Its ability to grow hairlike roots around its margin, and at the joint of any bend in the stem, virtually overnight, may also have something to do with its Werewolf Leaf nickname.

But it also is a universally beloved and beneficial plant, not just in Haiti, but all over the world. It’s known as Leaf of Life, Wonder of the World, and Miracle Plant. It”s called “katakataka” in the Philippines, which means Astonishing. It’s also called the Goethe Plant because Goethe himself loved to give out cuttings from it as do I. Soon you’ll understand why it’s so universally loved.

Like Vodou, it comes from Africa and has flourished in the Caribbean, and in tropical climates all over the world. Specifically, it comes from Madagascar, an island off the east coast of Africa. And like Vodou, it cannot be destroyed. Any effort to cut it up will just cause it to multiply, spread, proliferate. It knows where it comes from, and how to find water and tap into the source.

It was this plant’s exceptional creative power to put roots down, proliferate, and thrive that allowed it to naturalize all throughout the waistband of the earth. All it takes is one leaf and some water or soil, and a leaf or even a part of the margin of a leaf and soon you will have a new plant. My godmother gave me one cutting of this plant three years ago when I first moved to Austin. I grew it outside over a summer and it spread to neighboring beds and had leaves the size of dollar bills. When winter came, I took a few cuttings and grew them inside. When warm weather returned, I took cuttings from the indoor plant and planted them outside, where it again overflowed its boundaries. I have mailed cuttings to a friend in Pittsburgh during the winter and they survived. My godmother says you can even pin a leaf to a curtain in a sunny window and if you spray it regularly it will grow baby plants around its leaf margin.

The plant, medicinally, is good for almost everything. A tonic can be made by steeping the fresh leaves in boiling water (don’t boil the leaves themselves). Drink the tonic once a week or so to maintain the immune system. A slightly stronger infusion is good for colds or fever. It is anti diabetic; eating the whole leaf is good for balancing blood sugar. The leaf also helps with wound healing- heat a leaf in a pan like you would a tortilla- not too hot- and place on wound with a heating pad or hot water bottle over it. The juice can be used to treat kidney stones. It is anti-fungal, anti-ulcer, and is even used to treat cancer.

But all of its individual health-inducing and magical powers spring from its ability to survive, to regenerate, and to multiply, even when its "owners" would contain it. It spread all over the world because it was beloved by humans who kept it in pots and shared cuttings with their friends, but as soon as a leaf was allowed to fall onto the earth, babies sprung from its margins and it was off to the races. In some parts of the world, like Hawaii and Ecuador, it is considered an invasive species, and it is toxic to livestock if they're allowed to graze on it too much. All this is a testament to the fact that the plant has abundant life, genius, ambition, and energy of its own, and will make everything it touches-- every drop of water, ray of sunshine, and particle of soil-- its own. Just like Vodou.

n